Building for the Future: The Impact of the HSIPR Program

July 25, 2013

Written By Colin Leach

The U.S. Senate is currently considering a transportation funding bill that would provide $1.45 billion for Amtrak and $100 million for the higher speed rail. The Senate proposal stands in stark contrast to the House version, which slashes Amtrak’s budget to $1.05 billion and zeroes out the higher speed rail program.

As Congress debates the merit of investment in higher speed rail, it’s worth taking a look at the program’s history and successes. Created as part of the 2009 American Reinvestment and Recovery Act, the High Speed Intercity Passenger Rail Program was meant to establish the “foundation for a longer-term program to establish a network of high speed rail corridors.” Between 2009 and 2011, more than $10.1 billion in federal funds were allocated for projects within HSIPR’s domain. Of this total, $3.1 billion was actually allocated for projects in twenty-eight states and the District of Columbia.

Since 2011, however, no further projects have been funded despite existing allocations. This, according to Ryan Holeywell’s article in the May 2013 edition of Governing, is due to the fact no funds have been allocated to HSIPR since 2010. This refusal is part of a continued tendency towards inaction in the 113th Congress—see, for example, the House’s recent hostility towards the TIGER grant program—that does not bode well for near-term passenger rail investment. And it is not likely that the House’s attitude will change in the near future. Jeff Denham (R-CA), Chairman of the House Subcommittee on Railroads and Pipelines, has been going out of his way to target the California High-Speed Rail project, funded in part by HSIPR. Writing in the Fresno Bee on June 27th,Denham argued that the best policy for rail investment is “fix-it-first”, leaving potential new investments for an undetermined point in the future. He suggested that money spent on high speed rail would be better spent on highway projects, where it would have been “put to good use” much more quickly.

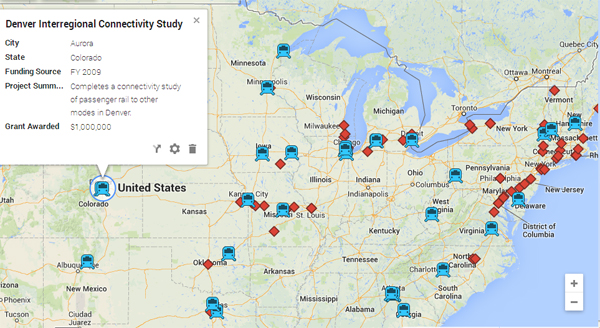

Contrary to the Congressman’s implications, HSIPR—in addition to sparking the development of the first world-class high speed rail line in the U.S.—has been quite effective at “fixing it.” While HSIPR has provided funds for many studies and preliminary engineering work on future high speed rail projects, it has also allowed for critical upgrades to existing corridors. Our map demonstrates HSIPR’s truly national coverage:

As may be seen on the above map, projects funded by HSIPR can take many forms. Whether they range from improvements as simple as the introduction of a passing siding on a small stretch of track, or as comprehensive as the acquisition and rehabilitation of lines more than 100 miles long, all HSIPR grants play a great role in improving existing services. Consider, for example, the St. Louis – Kansas City corridor. HSIPR funds no less than ten different projects aimed at improving service, including bridge replacements, elimination of highway grade crossings, and new signaling systems. When completed, these projects will enable faster travel time and increased frequencies on Amtrak’s Missouri River Runner, which is currently enjoying record patronage.

While California’s plans for 220 mph train service is the only HSIPR project that is currently constructing true high speed service, the program lays the groundwork for exactly these types of services. The California High Speed Rail project was only possible because of existing demand generated by Capitol Corridor, San Joaquin, and Pacific Surfliner services. It is reasonable to assume that HSIPR’s improvements to conventional services elsewhere will stimulate demand for more advanced high speed services in the future.

Such an approach is what prompted the development of the French TGV and the Japanese Shinkansen. Expanded capacity, increased frequencies, and decreased running times created a public demand that could only be met by totally new high-speed services. HSIPR’s investments are the first step towards that high-speed future.