It’s The Funding, Stupid

June 29, 2015

By Abe Zumwalt

It’s unfortunate that, given the blunt title of Matthew Yglesias’ recent piece “The Real Reason American Passenger Trains Are So Bad”, never once is the real problem—funding disparity—explicitly stated. Instead, the author dusts off a whole host of old arguments to explain why we don’t actually need further investment in passenger trains at all. Many of these seem to be honest misconceptions: that a whole new high-speed system must be built at enormous cost for passenger trains to become a more relevant option, instead of incrementally developing higher speed corridors; and that trains only serve endpoint to endpoint destinations like airplanes, instead of continuous corridors with vast permutations of possible trips taken. However, coming from a source that prides itself on technical analysis, the article was very disappointing to read.

Vox Says:

“[Foreign Countries a]re not doing a good job of managing 19th-century infrastructure, they're building brand new state-of-the-art high-speed rail infrastructure. To many people the question is: why not us?”

No country, with the possible exception of China, and only then on certain routes, started entirely from scratch. Countries with high-speed rail all actually do maintain their 19th-century networks in addition to their new lines, and in many cases, legacy networks form the base for the new, especially in crowded urban centers where land is scarce and expensive. If one bothers with looking at the early development of the most successful implementations of high speed rail, it is important to note that both the Shinkansen and TGV were built parallel to corridors which were already jammed to capacity with passengers.

The fundamental difference is that there was a real level of service offered before the high-speed lines were built. Amtrak’s 10 year, 50% ridership growth is impressive because its route structure is so anemic. The trend is indicative of tremendous amounts of pent-up demand. When trains run but three times a week in parts of the country, what other outcome is there but the perception of failure, despite a passenger load factor that beats the odds? 19th-century networks are precisely where others have started, building them out until demand for new trunk lines was justified. There are great increasing marginal returns to be had on our existing system if we make a real commitment to it, as indicated by increasing ridership everywhere, despite how few trains there are to begin with. It wouldn’t take hundreds of billions in high-speed infrastructure to see a real return—just reliable, regular service—but more on that in a moment.

Vox Says:

“[T]here's only one train per day […] departing D.C. a bit after four and arriving in Pittsburgh a bit before midnight. Of course, with the train so slow that there's no practical case for using it, there's little point in scheduling more trips. Megabus offers a slightly faster journey with two trips per day and charges $10 to $15, while Amtrak's fares start at $50.”

The train referred to is the Capitol Limited, which goes all the way to Chicago and stops in 16 communities along the way, the lions’ share of which boast no Megabus service at all. Like the rest of the system, the Capitol Limited has enjoyed steady and reliable ridership growth—so the statement “that there’s no practical case for using it” ignores the 225,000 people who rode the train last year. The train offers a value to its passengers—space, comfort, accessibility, not waiting on a random curbside (important when one accounts for the intersection between transportation and real estate)—that Yglesias has obviously not considered.

Vox Says:

“But even though plane flights are very polluting, they only add up to a modest 2.2 percent or so of total American carbon emissions. And of course for many journeys — Phoenix to Boston or Houston to Seattle — trains aren't a very plausible substitute anyway. So from an environmental perspective, too, massive rail expansion just doesn't look like a particularly compelling priority.”

The purpose of the intercity train is not to replace long-haul air travel, it is to provide real travel options where options are sparse if nonextant. The market that passenger trains truly offer an alternative to are private automobiles, which contribute 62 percent, the lion's share of our transportation pollution, according to the very graph used in the article. In the Long Distance Sector, a full 70 percent of ridership is derived from trips of well under 800 miles, happening anywhere on routes as long as 2,400 miles.

This distinction is critical. The idea that long-distance trains serve only their endpoints—say Seattle to Chicago—essentially ignores the 90 percent of ridership that travels nowhere near that distance. This discounts the importance of every town and city between major metropolises. It also discounts the several advantages of offering alternatives to automobiles—yes, there’s the pollution, but then even Vox has previously admitted that trains are 17 times safer than cars, and what’s more, that about 100 million people in this country can’t drive due to age or disability, and many of them do not currently have proper alternatives.

Vox Says:

“The way Amtrak is currently set up, there's no real incentive to undertake incremental improvements. The Northeast Corridor already generates an operating profit, which simply defrays losses elsewhere in the system. Making it run better doesn't generate any wins for the people who would have to do the work, and would plausibly just lead Congress to reduce subsidies. If the NEC were spun off as an independent entity — perhaps even a private company — then it could internalize the gains from improved service and seek private financing to make cost-effective investments.”

As an independent entity without connections to the long distance services, the Northeast Corridor would lose hundreds of thousands of passengers annually, putting a dent in that much-lauded operational surplus, which even left as it is now would never generate enough to pay for the $52 billion dollar backlog in capital maintenance. This backlog will chase any private interests away from the line—indeed, private operators in other countries rely on governmental assistance to subsidize the infrastructure they use, just like the current air and truck companies do stateside. Yes, one may cite new, private examples, like All Aboard Florida and the Texas Central Railway, but let’s not forget that those projects enjoy the luxury of existing or inexpensive right of way acquisition, as well as the fact that the former is equal parts property development project and transportation corridor.

We’re going to have to pay that backlog if we want the Northeast Corridor to continue to function well enough for Amtrak or any other entity. Yet we still needn’t spend hundreds of billions to make a significant impact: more conventional service needs to be offered just to meet current levels of demand nationwide. One comprehensive proposal to do just that would consume less than a full year of highway funding, as outlined by the DOT in the proposed Grow America act.

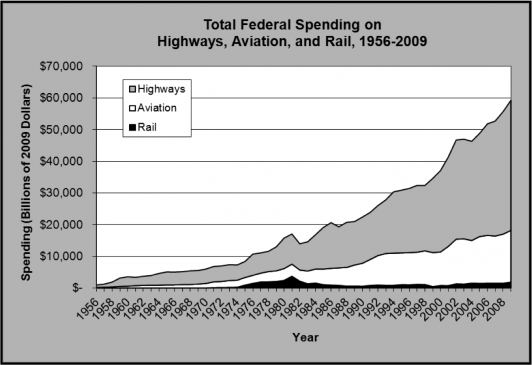

A reliable and increased level of funding over what we spend now— even an increase equivalent to 10 percent of the Highway Trust Fund’s annual outlays, or about $5 billion annually, as has been requested by the Obama Administration, would represent a 357 percent increase over current support for passenger trains. Congress has tried Vox’s implicit approach of micromanagement of current resources for 40 years, and it hasn’t worked. Yet the mode has in that time become ever more popular despite itself, and the entire system covers well over 80 percent of its operating costs, which makes it comparable in this way to Switzerland’s legendary federal railways.

When asking these questions in this growing country, one needs to look at the 50 billion pound elephant in the room: the vast disparity in federal support passenger trains receive when compared to airlines and roads. That’s the real reason why American passenger trains are so bad.